A couple of weeks ago, when I was finishing the Part 1 of this article/review, I was talking to a student of mine at my Worldbuilding class at the university about how much I hate the Hero’s Journey. Really. To bits.

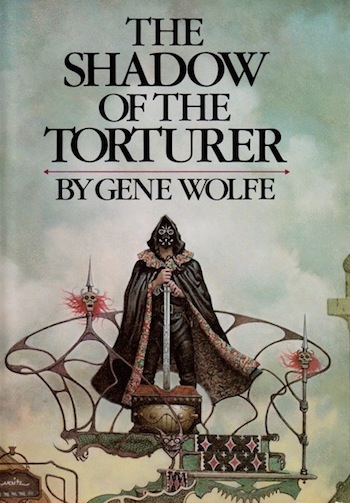

Naturally, that was a provocation of sorts: the reason I complain has more to do with the way everyone seems to overvalue and overuse this scheme, especially in films. Naturally, there are plenty of positive examples of the structure being used quite effectively, particularly in fantasy. The Lord of the Rings is one of the most mentioned, of course—but The Book of the New Sun tetralogy is one the most successful cases of the Hero’s Journey, IMHO, even if it doesn’t exactly fit the bill—and maybe just because that this series deserved much better recognition. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

In the previous article, our first installment about The Shadow of the Torturer, we followed Severian through his apprentice years in the Citadel, located in the city of Nessus, in the distant future of Urth, which is our Earth. He is a member of the Order of the Seekers for Truth and Penitence, which means he is training to become a torturer. One of his duties is to fetch books for one of the Order’s “clients” (as they call the prisoners due to be tortured and executed), the Chatelaine Thecla. Severian’s instructor Master Gurloes tells him who Thecla really is: she is of nobility, and a person of crucial interest to the Autarch, because her sister, Thea, has consorted with Vodalus (being the heart-shaped-faced woman he saw in the beginning of the novel), and he confides to Severian that maybe she can even be released.

In the meantime, Roche takes Severian to a courtesan house, the House Azure, where he will meet another woman, very similar to Thecla, and with whom he has the following dialogue:

“Weak people believe what is forced on them. Strong people believe what they wish to believe, forcing that to be real. What is the Autarch but a man who believes himself Autarch and makes others believe by the strength of it?

“You are not the Chatelaine Thecla,” I told her.

“But don’t you see, neither is she.”

[…]

“I was saying that the Chatelaine Thecla is not the Chatelaine Thecla. Not the Chatelaine Thecla of your mind, which is the only Chatelaine Thecla you care about. Neither am I. What, then, is the difference between us?”

What indeed? This apparent nonsensical dialogue, which should seem far too obvious to us, not to mention a bit exaggerated in its romanticism, is one of the keys to understand the role of memory in this novel. Remember two things: in Gene Wolfe’s work, everything is significant. And every narrator is unreliable.

Severian suspects (with the clarity of hindsight) that Master Gurloes had arranged for Roche to lead him to visit the House Azure often, so he wouldn’t become further involved with Thecla. But this strategy was in vain, for they end up making love. This leads to Severian’s undoing, for soon after Thecla receives notice that her execution may indeed proceed as planned. This is reinforced by a tour of the Matachin Tower on which Master Gurloes, along with Severian, takes Thecla, showing her many instruments of torture, including one which immediately stood out to me the very first time I read the book:

[This] is what we call the apparatus. It is supposed to letter whatever slogan is demanded in the client’s flesh, but it is seldom in working order.

It’s the same kind of apparatus found in Kafka’s story “In the Penal Colony.” Indeed, the bureaucratic attitude of Severian and his brothers of the Order bears some resemblance to the the world of Kafka’s characters. Naturally, this is not the only literary reference I noticed during my reading (but more on that later).

Thecla, knowing now she is going to be tortured and executed, asks Severian for a release. Not escape, but the release of death. She asks him only for a knife, which he gives her, knowing that he shouldn’t—and she kills herself. Severian promptly approached Master Gurloes and tells him what he’s done. Then he is imprisoned, living the life of a client, as he himself says, for ten days. In the eleventh day, he is summoned by Master Palaemon, who tells him that he should be executed for helping Thecla to escape justice, and that would only be the proper punishment—but their guild has no right in law to take life on their own authority. Severian asks sincerely that he be allowed to take his own life (bear in mind, reader, that sacrifice is a Catholic virtue, even if suicide is considered a mortal sin). Master Palaemon appreciates Severian’s attitude, but he declares that, instead, the young man is to become be a carnifex, one “who takes life and performs such excruciations as the judicators there decree. Such a man is universally hated and feared.”

He is not going to act as executioner there in Nessus, the capital, however:

There is a town called Thrax, the City of Windowless Rooms. […] They are in sore need in Thrax of the functionary I have described. In the past they have pardoned condemned men on the condition that they accept the post. Now the countryside is rotten with treachery, and since the position entails a certain degree of trust, they are reluctant to do so again.

At this point Severian receives from the hands of his master a sword—old, but still in very good condition, with a Latin name engraved on it: Terminus Est, whose translation is given as “This is the line of division” (again, an imprecision—one which I’m sure Wolfe knew about, but probably wanted to present this way as an example of how things change with the passage of time, to the point that some languages become almost inaccessible to the future generation—just as he did regarding the mottoes engraved on the dials in the Atrium of Time). Terminus Est means simply: “this is the end,” or “This ends here.” Quite appropriate for the sword of an executioner.

Leaving the Matachin Tower, the only home he had known, Severian severs (and I wonder if the choice of name for the protagonist would have anything to do with just that sense: a person who severs his connections, burns his bridges) all ties with his youth and his home, to never return—or, at least, as far as we can tell.

He leaves the city wearing the garment of his guild, a cloak described as fuligin (the material is blacker than black, or “soot,” for English-speaking readers—it’s a word that I had no difficulty translating in my mind because the Portuguese word for it is fuligem, with pretty much the same pronunciation). But even the simple act of leaving isn’t easy for Severian: he is soon imprisoned because of his strange clothes, and must explains his situation to the sheriff of the region, the lochage. The lochage seems to doubt him (Severian learns that, for some, the existence of Torturers is something of a myth, but not a well-liked one), but ends up letting him go on the provision that he buys new clothes, so he won’t be recognized by the tools of his trade.

Severian plans to do just that, the next day. In the meantime, he will spend his first night out of the Citadel sleeping in a small inn, where he must share a room with two men, only one of whom is in the room when he arrives: a giant by the name of Baldanders. In a scene strongly reminiscent of Moby-Dick, he shares a very uncomfortable bed. One aspect which certainly does not occur in the Melville book, however, is Severian’s dream: he sees a large leathery-winged beast, a chimera of sorts, with the beak of an ibis and the face of a hag, and a miter of bone on her head. In the distance, he sees all Urth as a purple desert, swallowed in the night. He wakes up startled, but then go to sleep again, to another dream, this one with naked women, with hair of sea-foam green and eyes of coral. They identify themselves as the brides of Abaia, a creature (maybe an elder god?) who is mentioned every now and then in the novel, “who will one day devour the continents.” (And it’s interesting to ponder what sort of role ancient gods might have in a narrative written by a Catholic author, and about a Christ-like figure.) In the dream, Severian asks them, “Who am I?” They laugh and answer that they will show him.

Then they present two figures to him, marionettes of sorts: a man made of twigs bearing a club, and a boy with a sword. The two fight each other, and, though the boy seems to win, in the aftermath both seem equally broken. Then Severian wakes up with the noise of the third occupant entering the room. He introduces himself as Dr. Talos; he and Baldanders are itinerant players for the stage, and are traveling north after a tour of the city. They invite Severian to go along.

Ever since my first reading of this novel, I have been intrigued by these two characters. Someone (perhaps my friend Pedro, who first lent me the book) had told me that the names “Talos” and “Baldanders” were mentioned in Jorge Luis Borges’s The Book of Imaginary Beings. This is true—the book stands apart from most of the old blind Argentine writer’s written works; rather than stories, poems, or essays, it takes the form of a small encyclopedia about creatures from folklore and myth. In it, Baldanders is described as a shapeshifter who appears in German stories in the 16th and 17th Centuries. Borges described him as “a successive monster, a monster in time,” depicted in the first edition of The Adventurous Simplicissimus (1669) as a kind of chimera. Talos is an artificial man, more particularly the man of bronze who serves as the guardian of Crete—a giant creature considered by some to be the work of Vulcan or Daedalus.

Why did Gene Wolfe choose those names for these characters? Seeing as every name in Wolfe’s work seems to carry a particular meaning based in etymology or allusion, or both (although those meanings might be arbitrary, like so much else in his work), it stands to reason that these two characters must have something about them that’s at least reminiscent of the creatures mentioned by Borges. In this first volume of the series, however, we are left with no clue. Is it possible that the giant Baldanders is a shapeshifter of some kind? What about Talos? Could he (as short in height as his companion is tall) be an artificial man? Probably—but unfortunately (or fortunately) I can’t remember the details, so for now I have chosen to let the mystery remain as I read on and perhaps be surprised again, to somehow recapture the sense of wonder I had when first reading this series.

After leaving the inn, the three have breakfast, and Talos manages to convince the waitress to join his troupe. Talos and Baldanders part ways with Severian, but he is made to promise that he will join them later, at a place called Ctesiphon’s Cross. He has no intention of rejoining them, but he will meet them again later. First, though, he tries to buy new clothes. During a walk through the streets of Nessus—filled with such marvels to the eye, ear, and nose as Baghdad in a story of the Thousand and One Nights—he stumbles upon a beautiful girl, and when he asks her where can he finds suitable clothes, she (who is also intrigued by his odd garments) takes him to a shop filled with articles of worn clothing. The shopkeeper—her brother—welcomes him and tries to buy his mantle and his sword, but Severian tells him he’s not there to sell, but to buy.

While they’re talking, another man enters the store. This man, an hipparch (or soldier, or, more accurately, “the commander of a xenagie of cavalry”, according to Michael Andre-Driussi’s Lexicon Urthus—I confess I used it a bit during the reading, but not too much) gives Severian a black seed the size of a raisin, and gets out immediately. The shopkeeker, frightened, tells him he must have offended an officer of the Household Troops, because that object is the stone of the avern: the symbol of a challenge to a monomachy, or duel.

Severian thinks that someone in the House Absolute—maybe the Autarch himself—has learned the truth about Thecla’s death and now seeks to destroy him without disgracing the guild.

In that moment, right after buying the new mantle which will disguise him, Severian makes what seems to be a small observation about himself, of no consequence:

The price seemed excessive, but I paid, and in donning the mantle took one step further toward becoming the actor that day seemed to wish to force me to become. Indeed, I was already taking part in more dramas than I realized.

In order to be prepared for the duel, Severian must get another avern (a kind of poisonous plant which can be yielded like a weapon), and the shopkeeper, Agilus, tells him that his sister Agia (the beautiful girl who brought him to the shop) will help him. They must hurry because the duel will happen in late afternoon, at the Sanguinary Field. Agia is quite confident that he will be killed, for he is young and has no experience in dueling. And she concludes: “It’s practically certain, so don’t worry about your money.”

Does that seem like a kind of scam to you, reader? Because it had always seemed so to me. But we need to go through the story a page at a time, always going forward. Pardon me if I skip over so many of the scenes and pages, but, as I had already remarked in in the first installment, Gene Wolfe accomplishes a thing of beauty in his novels: he manages to put so much information (he puts, not crams, and this is the significant thing here) that one must be very careful lest we skip some piece of information that’s fundamental to a better understanding of the narrative.

Scam or no scam, Agia takes Severian to the Botanic Gardens, where we will see a bit more of this strange world that is Urth. But, just before that, the vehicle they climb on to make the trip runs so rapidly through the labyrinthine streets that they crash into an altar, helping inadvertently to torch the Cathedral of the Pelerines, also known as the Cathedral of the Claw. The Pelerines are a band of priestesses who travel the continent. In the crash, Severian loses Terminus Est, but one of the priestesses delivers it back to him, telling him to use it to end quarrels, not to begin them. Then she asks him to return to them anything of value to them that he might have found. He hasn’t found anything. The priestess takes his wrists in his hands and declares that there is no guilt in him. She allows them to go on their way, even though her guards don’t agree. They continue on.

On the way to the Botanic Gardens, Agia explains to Severian that the Claw of the Conciliator is not a real claw, but a powerful relic in the form of a gem, even though she apparently does not attribute to it any significance beyond its possible financial value:

Supposing the Conciliator to have walked among us eons ago, and to be dead now, of what importance is he save to historians and fanatics? I value his legend as part of the sacred past, but it seems to me that it is the legend that matters today, and not the Conciliator’s dust.

But later—and this, reader, is one of the very few (intentionally given) spoilers I will offer here: of course Severian has the Claw, though he doesn’t know that at that moment—hence the priestess telling him he has no guilt (though she never said he didn’t have the jewel). And the Claw will prove to have a big role in Severian’s path to become the New Sun. But you already knew that, right?

See you in September 19th for the third installment of The Shadow of the Torturer…

Fabio Fernandes started writing in English experimentally in the ‘90s, but only began to publish in this language in 2008, reviewing magazines and books for The Fix, edited by the late lamented Eugie Foster. He’s also written articles and reviews for a number of sites and magazines, including Fantasy Book Critic, Tor.com, The World SF Blog, Strange Horizons, and SF Signal. He’s published short stories in Everyday Weirdness, Kaleidotrope, Perihelion, and the anthologies Steampunk II, The Apex Book of World SF: Vol. 2, Stories for Chip, and POC Destroy Science Fiction. In 2013, Fernandes co-edited with Djibrilal-Ayad the postcolonial original anthology We See a Different Frontier. He’s translated several science fiction and fantasy books from English to Brazilian Portuguese, such as Foundation, 2001, Neuromancer, and Ancillary Justice. In 2018, he translated to English the Brazilian anthology Solarpunk (ed. by Gerson Lodi-Ribeiro) for World Weaver Press. Fabio Fernandes is a graduate of Clarion West, class of 2013.

Arrrgh …. you are seriously going to make me want to re-read this book, and I really did not want to do that yet. But thank you for providing some kind of guide when I do, I was fairly lost and flailing the first time.

Wolfe had the power to write scenes that compel the attention, although I suspect that which particular scenes in any given work of his do so differs from reader to reader. For me it’s the first time Severian sees Agia – dressed in a worn and ragged dress of pavonine material, reaching up in the morning sun to unfurl the awning of their shop, the curve of her hip graced by the glow of her skin through a rip in the dress – struck me powerfully as the sort of thing that a young man would see once and never forget.

This is good timing. We just started a new chapter by chapter reading of New Sun. Chapter 3 comes out Sunday!

http://rereadingwolfe.podbean.com/

I hate to do this but: I think you mean “heart-shape-faced woman” and not “heart-shaped face woman”. Maybe you can just go with “heart-faced woman”?

Anyway, thank you for this. Like @1, I felt like I was floundering through this book. Somehow that didn’t stop me from greatly enjoying it regardless. It was about 10 years ago that I read it and this is bringing it all right back.

@@.-@: Fixed, thanks.

be a first read for me, thats why l like it here

@@.-@: Thanks! The reason I didn’t put “heart-faced woman” is that I chose to use Wolfe’s words.

Very nice, and does make me want to reread the book. (But your article on The Island of Doctor Death AOSAOS made me realize that I haven’t read all the stories collected there, so that will be first on my list.)

One thing: Although to us moderns it is natural to want to gloss Terminus Est as “this is the end,” it’s my understanding that Wolfe’s translation is in fact accurate—that in Latin, the primary meaning of terminus is “boundary,” and Terminus the name of the Roman god of border markers. (Some may remember this god being referenced by Neil Gaiman in the Sandman story “August”.) Hence: line of division.